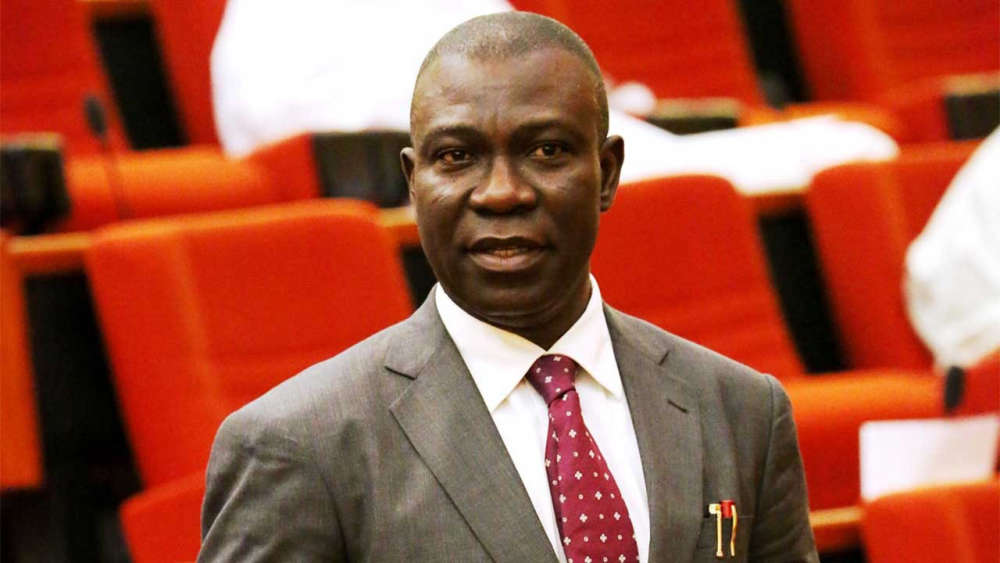

UK Shuts Down Nigeria’s Plea to Bring Ekweremadu Home — London Insists He Must Serve Full Sentence on British Soil

Former Nigerian lawmaker Ike Ekweremadu remains in UK prison after the government's rejection of Nigeria’s transfer request.

After weeks of diplomatic lobbying, the UK government firmly rejects Nigeria’s transfer request, citing justice, prison-system concerns, and the gravity of the organ-trafficking conviction.

The British government has formally rejected Nigeria’s request to transfer former Deputy Senate President Ike Ekweremadu back home to complete his prison sentence, ending weeks of high-level diplomatic efforts by Abuja and reinforcing the United Kingdom’s uncompromising stance on crimes linked to exploitation and modern slavery. The decision, confirmed by senior officials within the UK Ministry of Justice, means Ekweremadu will remain in the British correctional system until he completes his sentence—one that followed what the UK described as a grave violation of human dignity.

According to UK officials with knowledge of the process, Nigeria’s application was reviewed under the Transfer of Sentenced Persons framework, a legal mechanism that allows prisoners to serve the remainder of their sentences in their home countries under specific conditions. But after examining the Nigerian government’s submission, the Ministry of Justice concluded that the transfer was “not in the interests of justice”, adding that the UK could not obtain the necessary assurances that Ekweremadu would serve the remainder of his sentence without interference once repatriated. One UK official, speaking on record, stated: “Any prisoner transfer is at our discretion following a careful assessment of whether such a move aligns with justice and public safety. In this case, we have determined it does not.”

The decision comes despite a direct diplomatic push from President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s administration. Earlier this month, a Nigerian delegation led by Minister of Foreign Affairs Yusuf Tuggar and Minister of Justice Lateef Fagbemi travelled to London to negotiate Ekweremadu’s relocation. Their mission, described by insiders as “intense and strategic,” involved multiple engagements with senior UK officials in an attempt to secure approval for the transfer. Though details of these meetings were initially kept discreet, both parties were understood to have presented strong legal and humanitarian arguments.

For Nigeria, the request to have Ekweremadu returned home was rooted partly in diplomatic tradition—governments often seek the return of their high-profile citizens convicted abroad—and partly in what officials framed as humanitarian considerations. A senior Nigerian official familiar with the negotiation said the former lawmaker’s health, family challenges, and Nigeria’s capacity to supervise his sentence were part of the factors presented to the UK. “We made a legally grounded and compassionate case,” the official said. “But ultimately, the decision is theirs.”

London’s refusal, however, makes clear that the UK is unwilling to relax its posture on a conviction it views as emblematic of the fight against modern slavery. Several UK parliamentarians and senior justice officials have repeatedly emphasised that crimes involving exploitation—especially organ trafficking—are treated with the utmost seriousness. Another British official was quoted as saying: “The United Kingdom will not tolerate modern slavery in any form. Anyone convicted of such conduct must face the full consequences under UK law.”

Ekweremadu, now 63, was sentenced in May 2023 to nine years and eight months for his role in attempting to bring a young Nigerian man to the UK for the purpose of harvesting his kidney, which was intended for his daughter, Sonia. His wife, Beatrice, received a shorter sentence of four years and six months, while their associate, medical doctor Obinna Obeta, was handed ten years. The court found that the victim was recruited under false pretences, with promises of work and a better life, but was ultimately meant to be used as an organ donor without genuine informed consent. Judge Justice Jeremy Johnson, in delivering the sentence, described the scheme as a “despicable abuse of power and influence,” adding that the defendants “treated the young man as disposable.”

While Beatrice has since completed her sentence and returned to Nigeria, both Ekweremadu and Obeta remain in the UK prison system. For Ekweremadu, who served as Deputy Senate President for 12 years and was regarded as one of the most influential and experienced lawmakers of his generation, the conviction marked a dramatic fall from political relevance and global prestige.

In Nigeria, reactions to the UK’s rejection have been mixed. Supporters of the former lawmaker expressed disappointment, describing the decision as unnecessarily harsh, particularly given his long years of public service. Some political figures insist that Ekweremadu has already suffered extraordinary public humiliation and deserves a more compassionate resolution. Others argue that Abuja’s intervention was appropriate and consistent with diplomatic norms. “It is the duty of a responsible government to seek relief for its citizens abroad,” one senator said in a media interview. “Even if the request is not granted, the effort must be made.”

But on the other side of public opinion, many Nigerians—especially human rights advocates—applauded the UK’s decision, insisting that the rule of law should apply evenly, regardless of position or influence. Critics of the transfer request argue that Nigeria’s criminal justice system is often susceptible to political interference, raising legitimate questions about whether Ekweremadu would have been allowed to serve his full term if returned. A prominent activist remarked: “The UK simply exercised caution. Too many politically connected individuals return to Nigeria and miraculously regain freedom. The British authorities were not wrong to insist on credibility.”

The UK Ministry of Justice’s decision also speaks to a broader context. Over the past decade, Britain has increased its attention to human trafficking, organ trafficking, and exploitation-related crimes. The Modern Slavery Act, one of the strongest legal frameworks in the world, mandates severe penalties for offenders and emphasises the protection of vulnerable individuals. Within that legal climate, officials believe that relaxing Ekweremadu’s sentence—whether symbolically or logistically—would contradict a policy environment they have fought hard to protect.

With the rejection now official, the path forward is fairly clear: Ekweremadu will continue to serve his sentence in the UK until he qualifies for possible parole under British law, a process that is tightly regulated and immune to political influence. Though Nigeria may consider future appeals or alternative diplomatic channels, legal experts say the likelihood of success is extremely low unless the UK government reverses its position—something that, at the moment, appears improbable.

For Ekweremadu’s family, the reality is no less painful. His daughter, Sonia, whose kidney condition was central to the case, had earlier expressed heartbreak over her parents’ conviction. She has said publicly that she never wanted anyone to be exploited on her behalf. As for the victim at the centre of the case, he was placed under UK protective services and granted support, counselling, and accommodation.

The rejection of Nigeria’s request may close one chapter of the saga, but it opens another: the continuing diplomatic, moral, and political conversations about justice, power, privilege, and the boundaries of state intervention. For the Nigerian government, the episode also highlights the limits of diplomatic influence when dealing with legal systems that insist on strict independence. And for the UK, the message is unmistakable—no matter how powerful the individual, no matter how sensitive the circumstances, the integrity of the justice system will not be compromised.

What remains now is the long shadow of the crime itself, the international debate it continues to generate, and the reality that, for Ekweremadu, freedom will not come until the law has reached its final conclusion.

By Ekolense International Desk

Comments